How do you set your drag, and have you thought about this...?

If you own a big game fishing reel, you already know the basic mechanics of setting the drag.

But. . . not everyone uses the same technique, and equipment aside, there are essentially two basic methods commonly used to set the drag, and you may be surprised to know that results can vary dramatically.

For the sake of this discussion, let's ignore the type of drag gauge or scales you use to set the drag, except to note that other than the really expensive specialist drag gauges, what most of us use needs to be calibrated, because simple spring scales of any sort are pretty inaccurate. To calibrate your scales, just use a simple known weight (a bucket of water checked on a good set of digital kitchen or bathroom scales is fine) and check your drag scales against that, then either adjust the scales if there's a manual adjustment, or simply remember the difference and apply it every time you do your drags.

But it's how you actually set your drag which is important, and you'll probably be aware that the manufacturers of big game reels never tell you how to set the drag - they tell you how to adjust drag, and how the mechanics of the drag system work, but they don't recommend a preferred method for actually setting the drag, leaving that entirely up to the owner to figure out. And here's why. . .

Any quick check of the internet or even with the skippers in your own club will show you the two major schools of thought on drag setting. Some swear that the only way to set the strike drag is to apply a gentle, steady, and increasing pressure to the leader with the drag set to strike, and that the correct setting will be achieved when the reel starts to give line with this smooth pull off. It may take a couple of attempts, with an adjustment or two along the way. Manufacturers recommend using 25-33% of the line's breaking strain, but in this example, I'll be using the most popular setting of 33%.

The other school argues that you should set the drag up by applying a fairly vigorous pull that more closely simulates the abrupt loading that the rig will experience when a marlin grabs a lure and hooks up. Not a jerk, but a "vigorous pull".

I'm in this latter camp, and here's why. . .

Get one of your heavier rods and try both methods. Assuming for example that you try this with a 24kg rig, you should find the difference between the smooth and steady pull and the more abrupt vigorous pull will be up to about 50%, which is a huge variation.

In other words, if you're setting your 24kg rig drag at 8kg, to see this difference for yourself, first set the drag at 8kg using the smooth and steady pull method. Once you've set it that way, then leave the drag up at the strike button, and now use your scales to apply a fairly vigorous pull (not a jerk, but an aggressive pull like a rod experiences when loading up during a strike). Now take a look at what your scales read, and I'm betting that you'll find that it will be anything from 10-12kg, probably at the high end!

This means that if you set your drag using a smooth, easy pull at 8kg, the fish (which is neither smooth nor gentle in strike mode) is probably going to be loading up the line to around 12kg when it hooks up. OK so far, because you can argue that's still only 50% of breaking strain, so it should all be safe enough, albeit more than you want.

But here's the kicker. . . Let's say that like most of the pros and more successful (in terms of hookups per strike) skippers, you run your reels with your drag backed off below the strike setting when your pattern is set and you're trolling. So when our standard model aggressive marlin strikes and heads for the horizon, it's probably stripping line a bit faster due to the lower drag setting. In this hypothetical example, let's further assume that by the time your crew gets the rods cleared and the angler picks up the rod with the fish on it, pushes up the drag to strike, and settles down for the fight, the fish is well out there. Assuming that a big strong fish may have already run off with several hundred metres of line and is still carrying on like a mad thing on the surface half a kilometre away with a decent belly in the line, you could be down to as little as 50% of line capacity on the spool before this fight starts in earnest.

So, you will now be fighting with the effective radius of the half empty reel rather than the full reel you had when you set the drag. Modern hydrothermal drag systems are superb, but they're not perfect enough to automatically account for a changing spool radius, and as the effective radius of the spool of line reduces as line is stripped off, the drag applied by a drag system that was set with a full spool now increases exponentially. So in our hypothetical situation, if you've got enough line out to be down to about 50% of full spool radius, the drag system is now applying double the drag you set it at with a full spool.

Of course, some anglers would start backing off the drag lever a little in order to bring the drag being applied back closer to the 33% of breaking strain. However, if the drag remains at the strike detent, and you're down to a half spool with a drag setting that was originally done using the slow and steady pull method, guess what...? Yep, the fish could easily be loading your line up with . . . 24kg of drag! That's the breaking strain of the line in this argument, and when you throw in a few variables like the the fish having a mad moment and going for one more short burst of power, or even the angler stumbling and jerking the line, and you're looking at the dreaded "Twang" sound even though you reckon you did everything right and set your drag exactly at 8kg using the "steady pull" method that morning.

Now take the other example of the 24kg rig with the drag set by the "vigorous pull" method. The same fish hits the lure hard, loads the system up, and runs off with a few hundred metres of line. As before, at some point in the fight, you end up down at 50% of spool diameter, and thus double the actual drag being applied. At least in this instance, if the drag lever is still at strike, you'll only be loading the line to 16kg, still only 66% of its breaking strain.

Of course, I haven't bothered to talk about the effects of going to "sunset", or of how much drag a fish is applying when you're down to the last 100 metres of line on a tiny spool radius, or the variable but significant belly effect on line pressure, but it's not hard to work it all out, and it's all bad.

My point here though is simply to make you think a little about how you've been setting your drag, and what the dynamics of a big strike from your average healthy marlin are actually doing to your carefully calibrated and set rig. Even if you're not convinced by any of this, do me a favour when you next set your drag, and first set it using a smooth pull, then, without changing anything, give it an aggressive pull still using your drag scales, and load the rod up just like you see it load up when a marlin strikes and runs. You might be surprised at what your scales will read.

Also, always put your rod into a rod holder when you set the drag, and don't use a crewmember to simply hold the rod while you pull. Why. . . ? Because when a marlin strikes, the rod is going to be in a rigid rod holder, not in the hands of a more flexible human being. In the rod holder, it loads up properly, and releases at exactly the correct setting, so why not adjust that setting in the rigid rod holder instead of while a non-rigid person is holding it? No matter how firmly a person holds the rod, it won't be firmly enough to simulate a fixed rod holder, and so this is another variable you can do without that could adversely affect the accuracy of your drag calibration.

Finally, while talking about initial marlin strikes, it's worth digressing briefly to note that another thing I do on our boat is I have a calibration mark on all the drags on each reel that shows ⅔ of the set strike drag - for a full spool of course. In other words, if the strike drag is set as discussed above at ⅓ of breaking strain, I have another marking on the drag level mechanism of each reel that is in turn ⅔ of the set strike drag, or 8kg on a 37kg rig, 5(ish) kg on a 24kg rig, and so forth. This is where the drag levers are always set on my boat when we put the lures in the water, and it seems to consistently result in a better hookup or conversion rate on the boat. Once the angler picks up the rod after a fish is hooked up, he or she pushes the drag lever up to the full strike (⅔ of breaking strain) setting, and the fight goes ahead from there.

And one more thought in closing . . . while the state of your hook set is really the subject of a separate discussion, it pretty much goes without saying that all of the above assumes that your hooks are in perfect condition, or the effort your drag is applying to the tip of the hook at the moment a fish strikes is meaningless. Suffice to say for the moment that on every trip, you'll probably have at least 30 minutes of cruising before the fishing starts, and that can be well spent if at least one of your crew is sitting down with a file or a sharpening stone and bringing the points of the hooks on the lures you've chosen to go in the water that day to perfect needle sharpness. There is an associated long discussion to be had about the size of the barb on game hooks and the additional effort needed to get an excessively large barb to penetrate, but that can wait for another day. However, remember that if someone isn't sharpening your hooks every time they go in the water, then you're neglecting a critical part of the hookup equation, and no matter how assiduous you are about drag and drag calibration, it's only one of the number of critical elements that have to working perfectly in combination before you get a tag into a marlin.

No doubt all of this is the basis another argument or two for the Marlin Bar, but it's certainly worth thinking about. . .

This original article was written for the website in 2012, and has proven to be the most consistently popular "how to" piece on the entire website other than the daily Logbook and the weekly Flybridge pages, attracting dozens of readers per month. Since this was first publshed, I've fielded numerous questions on this matter, and have written smaller pieces on the same subject at various times. Recently, the related subject of drag and drag rise as effective spool diameter decreases came up again during a discussion with a European bluefin tuna expert, and I wrote a few paragraphs on the subject for the weekly Flybridge newsletter published on this website. Here's a copy of that discussion... some of it repeats what has been written above, but there's also a new discussion about Everol reels and a bit more about drag rise during a fight...

One of the discussions I had this week was with a game fisherman who also happens to be a physicist and fishes for Atlantic bluefin. His interest at the moment is all about drag settings, and the effect of decreasing effective spool diameter on drag as a fish strips line off a reel. As noted in the existing article about drag on this website, for a constant drag lever position, the drag exerted by a reel’s drag system steadily increases as the diameter of the spool decreases.

In very broad terms, if you set a strike drag off 33% on a full spool of line, without changing the position of the drag lever, that drag will have increased to about 50% of breaking strain after half the spool of line has been taken by a fish, and as you get down to the last few metres of line left on the spool, the drag will have increased to about 95% of the breaking strain - the real danger zone for the inexperienced angler. Of course, with an older reel and the older basic friction plate drag systems, this isn’t particularly reliable, because unlike the newer hydrothermal drags, the old gear can start to lose or increase drag as soon as it starts to overheat, and consequently, you can’t be sure of what’s really happening as the fish gets down into the bottom half of the spool.

When working with the old drags, anglers had to back off the drag as the spool got lower and the drag overheated, although that isn’t necessarily true of contemporary drag systems like those on current model Tiagras and Penn VSWs. Still, you can never be sure…

One highly respected Italian reel that has been on the market since 1958 is the Everol brand. Everol has been specialising in game reels engineered and built for catching Atlantic and Mediterranean bluefin tuna, and given how well the average Ferrari is put together in the same country of origin, it’s not unreasonable to describe the Everol reels as being the Ferraris of the game fishing business.

Interestingly, Everol hasn’t changed its basic design for decades, and while other reel manufacturers will argue that the Italians haven’t kept up with technology, it’s not hard to believe that they were using pretty advanced technology from the start, so maybe they aren’t really behind at all. Furthermore, as the Everol people would probably agree, if you’ve designed a perfect machine, why change it when there’s no need to…?

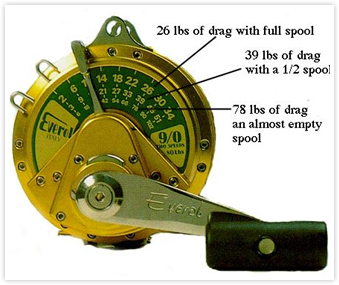

The Everol drag system was designed to be self cooling, using built-in finned marine grade stainless cooling elements that fan cool air over high temperature carbon fibre drag plates. In addition to the unique drag and cooling system, one of the standout features of all the Everol reels is a special drag calibration system that allows anglers to adjust drag during a fight to ensure that the reel is always exerting exactly the same drag regardless of whether the reel is full, or down to its last 100m of line.

Similarly, if an angler does decide to vary the drag during a fight, even if the desire is to increase the drag to overcome a fish that’s got you in a stalemate, at least the Everol system allows you to adjust to a precise level, rather than an educated guess.

No doubt this is a patented system. And even if you don’t subscribe to using it to back off or increase the drag accurately during a fight, it sure is nice to be able to consult the scale on the reel to give yourself an idea of just what drag you’re fighting with at any given time with a constant lever position.

As I mentioned earlier, you can argue both ways on this feature. Many anglers will still want to back off the drag when the spool diameter decreases as a fish on a big run strips line, but on the other hand, some skippers prefer to see the drag lever stay on the strike setting throughout a fight, so that as a particularly aggressive fish strips line, the drag increases proportionally, providing greater control over a fish threatening to spool the angler.

Regardless, there’s little doubt that circumstances may require a combination of both drag techniques at different times, but before deciding what to do under different fight conditions, you can’t really make a decision until you’re thoroughly familiar with the effect you’re having by changing the drag lever or by leaving it set.

While most of us have known about Everol reels for years, I must admit to never having seen or used one, although a good friend of mine from the Pensacola Game Fishing Club on the US east coast is a true believer, and needless to say, many of the blokes fishing in the Mediterranean swear by them.

Given the usual behaviour of a big tuna during a fight, where the fish generally goes deep and applies constant pressure once it tires, I can see a strong case for being able to accurately increase drag at any time during a fight with any tuna over about 75kg or so - at any spool level - so that between the angler and the skipper, the angle on the fish can be changed to help plane it up while knowing exactly what pressure you’re exerting on fish and line. Conversely, when fighting marlin, their unpredictable behaviour and proclivity to suddenly come up and have a tantrum on the surface halfway through a fight would mean to me that I’d be a little more circumspect about getting too fancy with drag changes unless I was working with a highly experienced angler on the rod.

But. . . not everyone uses the same technique, and equipment aside, there are essentially two basic methods commonly used to set the drag, and you may be surprised to know that results can vary dramatically.

For the sake of this discussion, let's ignore the type of drag gauge or scales you use to set the drag, except to note that other than the really expensive specialist drag gauges, what most of us use needs to be calibrated, because simple spring scales of any sort are pretty inaccurate. To calibrate your scales, just use a simple known weight (a bucket of water checked on a good set of digital kitchen or bathroom scales is fine) and check your drag scales against that, then either adjust the scales if there's a manual adjustment, or simply remember the difference and apply it every time you do your drags.

But it's how you actually set your drag which is important, and you'll probably be aware that the manufacturers of big game reels never tell you how to set the drag - they tell you how to adjust drag, and how the mechanics of the drag system work, but they don't recommend a preferred method for actually setting the drag, leaving that entirely up to the owner to figure out. And here's why. . .

Any quick check of the internet or even with the skippers in your own club will show you the two major schools of thought on drag setting. Some swear that the only way to set the strike drag is to apply a gentle, steady, and increasing pressure to the leader with the drag set to strike, and that the correct setting will be achieved when the reel starts to give line with this smooth pull off. It may take a couple of attempts, with an adjustment or two along the way. Manufacturers recommend using 25-33% of the line's breaking strain, but in this example, I'll be using the most popular setting of 33%.

The other school argues that you should set the drag up by applying a fairly vigorous pull that more closely simulates the abrupt loading that the rig will experience when a marlin grabs a lure and hooks up. Not a jerk, but a "vigorous pull".

I'm in this latter camp, and here's why. . .

Get one of your heavier rods and try both methods. Assuming for example that you try this with a 24kg rig, you should find the difference between the smooth and steady pull and the more abrupt vigorous pull will be up to about 50%, which is a huge variation.

In other words, if you're setting your 24kg rig drag at 8kg, to see this difference for yourself, first set the drag at 8kg using the smooth and steady pull method. Once you've set it that way, then leave the drag up at the strike button, and now use your scales to apply a fairly vigorous pull (not a jerk, but an aggressive pull like a rod experiences when loading up during a strike). Now take a look at what your scales read, and I'm betting that you'll find that it will be anything from 10-12kg, probably at the high end!

This means that if you set your drag using a smooth, easy pull at 8kg, the fish (which is neither smooth nor gentle in strike mode) is probably going to be loading up the line to around 12kg when it hooks up. OK so far, because you can argue that's still only 50% of breaking strain, so it should all be safe enough, albeit more than you want.

But here's the kicker. . . Let's say that like most of the pros and more successful (in terms of hookups per strike) skippers, you run your reels with your drag backed off below the strike setting when your pattern is set and you're trolling. So when our standard model aggressive marlin strikes and heads for the horizon, it's probably stripping line a bit faster due to the lower drag setting. In this hypothetical example, let's further assume that by the time your crew gets the rods cleared and the angler picks up the rod with the fish on it, pushes up the drag to strike, and settles down for the fight, the fish is well out there. Assuming that a big strong fish may have already run off with several hundred metres of line and is still carrying on like a mad thing on the surface half a kilometre away with a decent belly in the line, you could be down to as little as 50% of line capacity on the spool before this fight starts in earnest.

So, you will now be fighting with the effective radius of the half empty reel rather than the full reel you had when you set the drag. Modern hydrothermal drag systems are superb, but they're not perfect enough to automatically account for a changing spool radius, and as the effective radius of the spool of line reduces as line is stripped off, the drag applied by a drag system that was set with a full spool now increases exponentially. So in our hypothetical situation, if you've got enough line out to be down to about 50% of full spool radius, the drag system is now applying double the drag you set it at with a full spool.

Of course, some anglers would start backing off the drag lever a little in order to bring the drag being applied back closer to the 33% of breaking strain. However, if the drag remains at the strike detent, and you're down to a half spool with a drag setting that was originally done using the slow and steady pull method, guess what...? Yep, the fish could easily be loading your line up with . . . 24kg of drag! That's the breaking strain of the line in this argument, and when you throw in a few variables like the the fish having a mad moment and going for one more short burst of power, or even the angler stumbling and jerking the line, and you're looking at the dreaded "Twang" sound even though you reckon you did everything right and set your drag exactly at 8kg using the "steady pull" method that morning.

Now take the other example of the 24kg rig with the drag set by the "vigorous pull" method. The same fish hits the lure hard, loads the system up, and runs off with a few hundred metres of line. As before, at some point in the fight, you end up down at 50% of spool diameter, and thus double the actual drag being applied. At least in this instance, if the drag lever is still at strike, you'll only be loading the line to 16kg, still only 66% of its breaking strain.

Of course, I haven't bothered to talk about the effects of going to "sunset", or of how much drag a fish is applying when you're down to the last 100 metres of line on a tiny spool radius, or the variable but significant belly effect on line pressure, but it's not hard to work it all out, and it's all bad.

My point here though is simply to make you think a little about how you've been setting your drag, and what the dynamics of a big strike from your average healthy marlin are actually doing to your carefully calibrated and set rig. Even if you're not convinced by any of this, do me a favour when you next set your drag, and first set it using a smooth pull, then, without changing anything, give it an aggressive pull still using your drag scales, and load the rod up just like you see it load up when a marlin strikes and runs. You might be surprised at what your scales will read.

Also, always put your rod into a rod holder when you set the drag, and don't use a crewmember to simply hold the rod while you pull. Why. . . ? Because when a marlin strikes, the rod is going to be in a rigid rod holder, not in the hands of a more flexible human being. In the rod holder, it loads up properly, and releases at exactly the correct setting, so why not adjust that setting in the rigid rod holder instead of while a non-rigid person is holding it? No matter how firmly a person holds the rod, it won't be firmly enough to simulate a fixed rod holder, and so this is another variable you can do without that could adversely affect the accuracy of your drag calibration.

Finally, while talking about initial marlin strikes, it's worth digressing briefly to note that another thing I do on our boat is I have a calibration mark on all the drags on each reel that shows ⅔ of the set strike drag - for a full spool of course. In other words, if the strike drag is set as discussed above at ⅓ of breaking strain, I have another marking on the drag level mechanism of each reel that is in turn ⅔ of the set strike drag, or 8kg on a 37kg rig, 5(ish) kg on a 24kg rig, and so forth. This is where the drag levers are always set on my boat when we put the lures in the water, and it seems to consistently result in a better hookup or conversion rate on the boat. Once the angler picks up the rod after a fish is hooked up, he or she pushes the drag lever up to the full strike (⅔ of breaking strain) setting, and the fight goes ahead from there.

And one more thought in closing . . . while the state of your hook set is really the subject of a separate discussion, it pretty much goes without saying that all of the above assumes that your hooks are in perfect condition, or the effort your drag is applying to the tip of the hook at the moment a fish strikes is meaningless. Suffice to say for the moment that on every trip, you'll probably have at least 30 minutes of cruising before the fishing starts, and that can be well spent if at least one of your crew is sitting down with a file or a sharpening stone and bringing the points of the hooks on the lures you've chosen to go in the water that day to perfect needle sharpness. There is an associated long discussion to be had about the size of the barb on game hooks and the additional effort needed to get an excessively large barb to penetrate, but that can wait for another day. However, remember that if someone isn't sharpening your hooks every time they go in the water, then you're neglecting a critical part of the hookup equation, and no matter how assiduous you are about drag and drag calibration, it's only one of the number of critical elements that have to working perfectly in combination before you get a tag into a marlin.

No doubt all of this is the basis another argument or two for the Marlin Bar, but it's certainly worth thinking about. . .

This original article was written for the website in 2012, and has proven to be the most consistently popular "how to" piece on the entire website other than the daily Logbook and the weekly Flybridge pages, attracting dozens of readers per month. Since this was first publshed, I've fielded numerous questions on this matter, and have written smaller pieces on the same subject at various times. Recently, the related subject of drag and drag rise as effective spool diameter decreases came up again during a discussion with a European bluefin tuna expert, and I wrote a few paragraphs on the subject for the weekly Flybridge newsletter published on this website. Here's a copy of that discussion... some of it repeats what has been written above, but there's also a new discussion about Everol reels and a bit more about drag rise during a fight...

One of the discussions I had this week was with a game fisherman who also happens to be a physicist and fishes for Atlantic bluefin. His interest at the moment is all about drag settings, and the effect of decreasing effective spool diameter on drag as a fish strips line off a reel. As noted in the existing article about drag on this website, for a constant drag lever position, the drag exerted by a reel’s drag system steadily increases as the diameter of the spool decreases.

In very broad terms, if you set a strike drag off 33% on a full spool of line, without changing the position of the drag lever, that drag will have increased to about 50% of breaking strain after half the spool of line has been taken by a fish, and as you get down to the last few metres of line left on the spool, the drag will have increased to about 95% of the breaking strain - the real danger zone for the inexperienced angler. Of course, with an older reel and the older basic friction plate drag systems, this isn’t particularly reliable, because unlike the newer hydrothermal drags, the old gear can start to lose or increase drag as soon as it starts to overheat, and consequently, you can’t be sure of what’s really happening as the fish gets down into the bottom half of the spool.

When working with the old drags, anglers had to back off the drag as the spool got lower and the drag overheated, although that isn’t necessarily true of contemporary drag systems like those on current model Tiagras and Penn VSWs. Still, you can never be sure…

One highly respected Italian reel that has been on the market since 1958 is the Everol brand. Everol has been specialising in game reels engineered and built for catching Atlantic and Mediterranean bluefin tuna, and given how well the average Ferrari is put together in the same country of origin, it’s not unreasonable to describe the Everol reels as being the Ferraris of the game fishing business.

Interestingly, Everol hasn’t changed its basic design for decades, and while other reel manufacturers will argue that the Italians haven’t kept up with technology, it’s not hard to believe that they were using pretty advanced technology from the start, so maybe they aren’t really behind at all. Furthermore, as the Everol people would probably agree, if you’ve designed a perfect machine, why change it when there’s no need to…?

The Everol drag system was designed to be self cooling, using built-in finned marine grade stainless cooling elements that fan cool air over high temperature carbon fibre drag plates. In addition to the unique drag and cooling system, one of the standout features of all the Everol reels is a special drag calibration system that allows anglers to adjust drag during a fight to ensure that the reel is always exerting exactly the same drag regardless of whether the reel is full, or down to its last 100m of line.

Similarly, if an angler does decide to vary the drag during a fight, even if the desire is to increase the drag to overcome a fish that’s got you in a stalemate, at least the Everol system allows you to adjust to a precise level, rather than an educated guess.

No doubt this is a patented system. And even if you don’t subscribe to using it to back off or increase the drag accurately during a fight, it sure is nice to be able to consult the scale on the reel to give yourself an idea of just what drag you’re fighting with at any given time with a constant lever position.

As I mentioned earlier, you can argue both ways on this feature. Many anglers will still want to back off the drag when the spool diameter decreases as a fish on a big run strips line, but on the other hand, some skippers prefer to see the drag lever stay on the strike setting throughout a fight, so that as a particularly aggressive fish strips line, the drag increases proportionally, providing greater control over a fish threatening to spool the angler.

Regardless, there’s little doubt that circumstances may require a combination of both drag techniques at different times, but before deciding what to do under different fight conditions, you can’t really make a decision until you’re thoroughly familiar with the effect you’re having by changing the drag lever or by leaving it set.

While most of us have known about Everol reels for years, I must admit to never having seen or used one, although a good friend of mine from the Pensacola Game Fishing Club on the US east coast is a true believer, and needless to say, many of the blokes fishing in the Mediterranean swear by them.

Given the usual behaviour of a big tuna during a fight, where the fish generally goes deep and applies constant pressure once it tires, I can see a strong case for being able to accurately increase drag at any time during a fight with any tuna over about 75kg or so - at any spool level - so that between the angler and the skipper, the angle on the fish can be changed to help plane it up while knowing exactly what pressure you’re exerting on fish and line. Conversely, when fighting marlin, their unpredictable behaviour and proclivity to suddenly come up and have a tantrum on the surface halfway through a fight would mean to me that I’d be a little more circumspect about getting too fancy with drag changes unless I was working with a highly experienced angler on the rod.